I got my first Bible before I was old enough to read it: it was a small New Testament with a white cloth cover. My mom had lovingly sewn lace around the edges and cross-stitched a lamb onto the front. I was just learning to write my name when she gave it to me, and I didn’t hesitate to use every blank page for practicing that important skill.

As someone who was raised in a missionary family, I’ve since read dozens of Bibles: literal translations, paraphrased translations, kids’ Bibles, themed Bibles, Bibles in other languages. Some did a better job of holding my attention than others did.

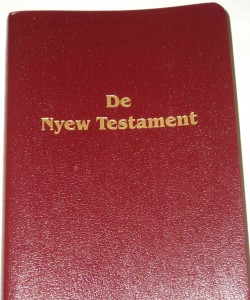

Last year, I celebrated my thirty-first birthday in Charleston, South Carolina. While I was there, I wandered into a bookshop, where I discovered a Gullah New Testament. The store was about to close (and I try not to be an impulse shopper), but I couldn’t leave the store without buying that book. There was something so intriguing about it. Of all the Bibles that I had read, I had never seen anything like this one: it wasn’t in English, but as I read it, I could understand almost every word.

The Gullah are descendants of African slaves brought over from Sierra Leone. There are almost half a million of them living along the Eastern coast of the United States, from North Florida to North Carolina. According to Joseph A. Opala, who wrote about the Gullah on www.yale.edu, “Because of their geographical isolation and strong community life, the Gullah have been able to preserve more of their African cultural heritage than any other group of Black Americans. They speak a creole language similar to Sierra Leone Krio, use African names, tell African folktales, make African-style handicrafts such as baskets and carved walking sticks, and enjoy a rich cuisine based primarily on rice.”

To give you a feel for the language, here is a verse from the Gullah New Testament. If you know the Nativity story, you will probably understand it. It’s about the wise men visiting Jesus, found in Matthew 2:11, “Dey gone eenta de house, an day see de chile dey wid e modda, Mary. Den dey kneel down fo de chile an woshup um op. An dey open op dey bag an tek out de rich ting dey beena cyaa long wid um fa gii de chile. Dey gim gole, frankincense, an myrrh.”

On the same trip to Charleston, I met a friendly Gullah anthropologist at The Old Slave Mart Museum. She had been raised in a Gullah family, she spoke fluent Gullah, and she was now educating people about her culture through the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. We talked about her cultural experiences and the Gullah New Testament, which she was also fascinated by. She had been reading it “all the time.” Her mom had been trying to get her to read the Bible in English (before the American Bible Society put out the Gullah New Testament in 2005). And when her mom found out that she had been reading the Gullah version, she told her, “If only I had known that there was a way to get you to read the Bible!”

Having a Gullah New Testament got me to open the Bible more frequently, too. It allowed me to engage in scripture from a completely fresh perspective. I was able to look at the Bible like I had as a small child, figuring out its words for the very first time.

Lisah VandeRiet

Rachel

Maurice

Rachel